Written and edited by Brian Cafritz

Whether it is an injury caused by a sidewalk defect, a parking lot hazard, a product or shelving display, or even a broken glass or bowl, retailers and restaurants regularly defend negligence cases by arguing that notice is not required for Open and Obvious conditions.

At its heart, the Open and Obvious doctrine relieves a defendant from the duty to warn of a condition if that condition is clearly visible and noticeable to the Plaintiff. The idea is that warnings are not necessary when the Plaintiff knows (or should know) of the danger by simply paying attention. “If a person trips over an ‘open and obvious condition or defect’ she is ‘guilty of contributory negligence as a matter of law,’ unless there is a legally valid justification for failing to observe the defect. Scott v. City of Lynchburg, 241 Va. 64, 66, 399 S.E.2d 809, 810, 7 Va. Law Rep. 1300 (1991). Stated differently, ‘where a defect is open and obvious to persons using a sidewalk it is their duty to observe the defect,’ and ‘[w]here there is no excuse for not seeing the defect one cannot recover.’ Town of Va. Beach v. Starr, 194 Va. 34, 36, 72 S.E.2d 239, 240 (1952).” Estep v. Xanterra Kingsmill, LLC, 2017 U.S. Dist. Lexis 43706 (E.D. Va., March 20, 2017). The doctrine has been alive and well for generations, but a recent decision by Judge Mark Davis of the US District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia has created a ripple in the way the doctrine is analyzed.

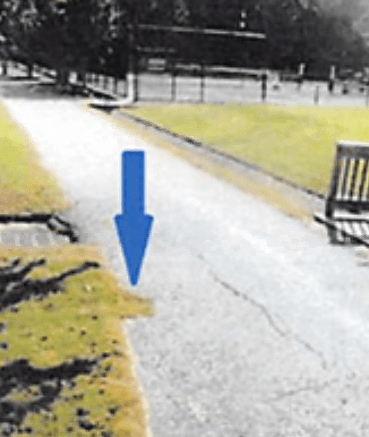

The case is Estep v. Xanterra Kingsmill, LLC, 2017 U.S. Dist. Lexis 43706 (E.D. Va., March 20, 2017). In Estep, plaintiff participated in a tennis league held at the Kingsmill tennis courts. While waking on an asphalt path towards the courts, Plaintiff fell on hole beneath a grassy patch that intruded to the left edge of the asphalt patch. (See photo). There was a full 5 feet of open pathway to the right of the grass patch. At the time of her fall, Plaintiff was alone on the path and undistracted. Many other people safely used the path with no known injuries. There had been no complaints to the defendant of the condition.

Plaintiff conceded that she could have seen the grass, but she did not recognize it as a tripping hazard or know that there was a hole or depression under the grassy area that would cause her to fall. Her argument was that she did not know there was a hole or depression under it. In other words, she argued that knowledge of an open and obvious condition is not the same as an open and obvious hazard.

Plaintiff conceded that she could have seen the grass, but she did not recognize it as a tripping hazard or know that there was a hole or depression under the grassy area that would cause her to fall. Her argument was that she did not know there was a hole or depression under it. In other words, she argued that knowledge of an open and obvious condition is not the same as an open and obvious hazard.

The defendant argued that the law makes no such distinction, but the Court agreed with Plaintiff, noting that reasonable minds could differ on whether the grassy area represented a tripping hazard or whether it was unreasonable for her to step on grass that was level with the path and within the path’s borders.

For this reason, the court rejected the defendant’s motion for summary judgment and instead ruled that there exists a distinction between an open and obvious condition and an open and obvious hazard. “It is not enough that an object be plainly visible to constitute an open and obvious hazard, the plaintiff must also have reason to appreciate the nature of the harm posed by the object.” Cunningham v. Delhaize Am., Inc., U.S. Dist. LEXIS 140655, 2012 WL 4503150, (W.D. Va. Sept. 27, 2012). Because the Judge could not definitively say that the grass patch was an obvious hazard or hat she should have avoided it, he ruled that the question must be decided by the jury.

This ruling is important, because it creates a subtle nuance for Plaintiff’s to exploit. Now a Plaintiff can say that he or she saw the condition, but did not recognize the danger in it. This position will make it more likely that a jury question will exist, and summary judgment will be harder to obtain. But this argument can be also constrained to some degree. Whether a hazard is open and obvious must be judged by an objective standard, i.e., based on what a reasonable person would consider dangerous. It is not determined by the subjective standard of what a particular plaintiff felt or believed. Indeed, despite the language relied upon in the above quote from the Cunningham case, Judge Davis is clear in his opinion that the determination is still based on what a reasonable person would consider dangerous. However, the Plaintiff’s bar is likely to seize on this distinction and argue that the Plaintiff did not recognize the danger despite seeing the condition. This is not the standard, and defense counsel should be quick to recognize the difference.

If you have any questions about the Open and Obvious doctrine and how it may apply to your situation, KPM LAW attorneys are ready to answer the call.